Notes on the L Train

On the other side of the train, someone whispers into a friend’s ear, laughing through their own joke: “I didn’t know they went this far.”

A gaggle of young twenty-somethings enter the L train, all dressed in light blue jeans and variations of a black top. It’s Saturday evening and the city wants to dance. The train closes its doors behind them, rolling away from Broadway Junction and into East New York. The group of women talk amongst themselves about how New York has changed so much. One of them declares: “Murray Hill is the new West Village, Lower East Side is the new Murray Hill, Williamsburg is the new Lower East Side, Bed-Stuy is the new Williamsburg, and Bushwick… Well, Bushwick is Bushwick.” The women laugh and agree.

Neither party heard each others’ comments. One can imagine they wouldn’t appreciate each other’s words.

Much can be said about this non-exchange of words. One obvious reading is about gentrifiers (as well as the real estate industrial scheme at-large) and their ability to flatten real living communities into a marketable cultural geography. However, something that gets lost within this market-focused discourse is a question of the role of government in exacerbating these neighborhood changes. Especially after the past two years of the pandemic—when both City and State failed to regulate an unruly housing market and left people with no choice but to routinely pack up their home in search of housing that fits their budget—New York City has not seen any reprieve in its ever shifting cultural geography.

More than 300,000 people moved out of New York City within the first year of the pandemic, an exodus that radically shifted the city’s social fabric. Real estate developers and landlords, with an eye on their bottom line, offered marked down prices —“Covid deals”—to attract renters. People who would not otherwise have had the financial means to live in one neighborhood suddenly found themselves embedded in a new community they previously had little or no attachment to.

Both exodus and mass internal migration were phenomena occurring especially because of the housing market, rupturing the cultural geography of New York City as we knew it. As fast as you can jump a turnstile, who gets off at what stop becomes harder to predict.

Yet, media and politicians alike are hell bent on telling the world that “More People Are Moving To Manhattan Than Before The Pandemic.” They’ll give you “23 Reasons” why “New York is back, baby!” despite the ever high COVID-19 figures.

But Covid denial makes for a poor chaser to hide the horrid taste of housing deregulation. New York State’s decision to end the eviction moratorium, implemented to mitigate the economic hardships of the pandemic, has wrought a rapid, wide-spread spike in evictions. There have been at least 2,000 eviction cases filed each week since March, a rate so high there is now a shortage of public defenders to ensure a right-to-counsel in our housing courts. Moreover, the end of Covid leases has left the housing market in disarray. After the New York State legislature failed to pass the incredibly popular Good Cause bill — which would limit rent increases by the rate of inflation or the Consumer Price Index, whichever one was higher — the unregulated housing market saw a morally bankrupt wave of price gouging. Renters across New York State saw their apartments increase by 30%, 40%, sometimes by even 100%. Those once treasured Covid deals are back on the market for significantly more than their listing prices before the pandemic, a clear sign of price gouging and leading to a wave of de facto evictions at lease end. All of this, preventable.

The exodus may have ceased, but at present New York City faces yet another wave of widespread displacement. And with it, another shift in the cultural geography of this city. The people of the L Train know this well. Their Saturday commute to whatever party or gathering has inspired the same observation. New Yorkers are accustomed to talking about how fast a neighborhood can change, but both pandemic and a government unwilling to regulate the housing market has exacerbated its speed.

When housing justice organizers talk about how evictions destabilize neighborhoods, it includes our cultural geography. After all, we party here and not there because of how easy we can access cultural spaces from our homes. At the heart of an appreciation for a city’s cultural geography is place-making: our ability to create distinct spaces worthy of celebration, preservation, and, yes, dancing.

The train opens its doors. Both parties leave at the same stop, off to sway their hips as far as the city will allow.

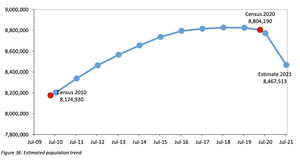

Cornell Program on Applied Demographics. 2021 County and Economic Development Regions Population Estimates. March, 2022.

Data For Progress. Good Cause. May, 2022.